Whether pilfered for personal use or stolen in bulk for diversion, opportunistic or planned, the theft of medicines has a broad impact that increases risk to public health and risks the integrity of the medicine supply chain. Considering the amount of UK medicines distributed, the proportion of theft is low, however, this series of blog posts aims to assist distributors to improve security standards.

Work carried out by the MHRA Enforcement team has a direct positive impact on reducing illegal supply of Z-drugs, as described in a recent MHRA Press Release. Although Z-drugs are not only illegally obtained via theft, the risk to public health of diverted medicines is the same.

As a GDP inspector, what I will be covering in this and the posts that follow is independent but complementary to the Enforcement Z‑drug work. My aim is to share best practice within industry of developing a good security culture to help maintain the strong reputation of the UK medicine supply chain. I will cover prevention of theft concerned with all types of medicine, and security associated with storage and transportation.

What is contained within these posts is already captured within GDP expectations and is described in general terms to account for the diversity in distribution models and types of theft.

The potential impact of theft is widespread, for example:

- delay of essential medicine supply to a patient

- diversion of medicines to unauthorised consumers

- diversion into the authorised supply chain of medicines damaged by handling in inadequate conditions

- increased cost of medicines due to cost of replacement and additional preventive measures

- increased insurance cost to distributors

- loss of good reputation of distributors

- supports the operation of organised criminal groups

So, what is the problem?

Theft of medicines takes several forms. At the lower end of the scale, opportunistic pilfering of individual packs for personal use may occur, while towards the other extreme, various forms of theft models occur depending on the organised crime groups involved.

A recent blog post by Peter Brown, GDP Senior Inspector, describes some of the approaches taken by criminals to use deception to obtain stock or divert falsified medicine back into the legitimate supply chain.

In a separate post, Tony Orme, Senior Lead GDP Inspector, outlines measures wholesalers can take to reduce the chance of dealing with unauthorised suppliers or customers.

Aside from deception, theft can involve overt warehouse break-in or theft from (or of) transport, which can be very traumatic for staff.

Theft may have a relatively low health risk for the individual where theft is pilfering of a general sale list (GSL) item for personal use, such as aspirin.

The risk to public health rapidly increases where the theft is:

- intended for onward supply

- of bulk quantity

- of P (pharmacy medicines) or POM (prescription-only medicines) or medicine with potential for abuse (such as cough syrup)

- of items in short or restricted supply

- of items which have specific administration or storage conditions, for example cold chain.

The measures taken to protect against theft and the approach taken to reporting theft of medicine to MHRA, should be proportionate to the risk to public health. For many distributors, the measures taken to deal with and report theft are primarily based on financial value and independent of public health risk, with a reactive rather than proactive approach. This indicates inadequate quality risk management and is often associated with weak preventive actions.

Survey of security awareness

To gain a clear picture of the status within industry, I posed the following 4 questions at the 2017 GDP symposium (attended by just over 800 delegates from the pharmaceutical industry).

Q1. What sort of company do you work for?

This question was raised in order to understand the composition of survey respondents. Data was excluded from summaries where company type was not entered or where the respondent came from outside the industry, such as other regulators.

Delegates who came from companies that specialised in transportation were very welcome, as distributors often do not understand how their products reach their customers, have no formal vendor qualification process to select couriers and no formal oversight, such as audits. For this reason, I will write specifically about transportation in a later blog.

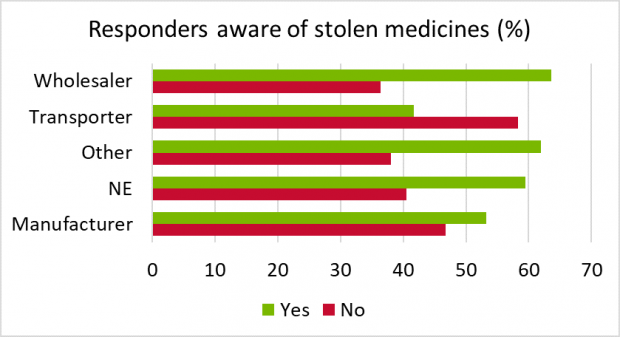

Q2. Are you aware of specific examples of any medicines being stolen during the last 12 months?

This question was raised to determine whether delegates were aware of stock stolen from their own company (which may not be reported externally) or if they had noticed any news or industry reports of stock stolen anywhere else.

Of the manufacturers, wholesalers and transport companies who responded, 58% were aware of medicine theft and 42% not aware. This ratio was similar to the proportion that did not enter their company type (NE). It is possible that many of the delegates were not directly responsible for implementing security measures in their company. The 42% that were not aware indicates an opportunity in those companies for improvement in developing good security awareness and security culture. By maintaining awareness of theft of medicines, employees can stay more security-conscious and help safeguard public health, as well as help protect their own safety.

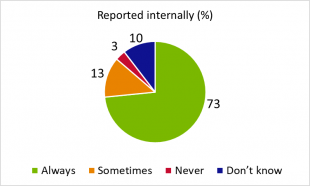

Q3. Does your company require potentially missing or stolen medicines to be reported internally?

Of those companies that responded in the survey, the ratio of responses did not vary much between different company types so the responses are consolidated in the pie chart. Most delegates appeared comfortable in reporting stock losses within their company, and for those who only reported loss on some occasions, there may be various factors that caused a company to report or not report.

Of those companies that responded in the survey, the ratio of responses did not vary much between different company types so the responses are consolidated in the pie chart. Most delegates appeared comfortable in reporting stock losses within their company, and for those who only reported loss on some occasions, there may be various factors that caused a company to report or not report.

When stock is lost at a third-party storage site or while in transit with a courier this may be more likely to be reported internally by the company owning the stock, especially where insurance claims are made or police involved.

Regular small item loss may be so common that such loss is accepted as the norm. This may be the case where pilfering for personal use exists.

Another cause for loss - which is more prevalent in some sectors - is the supply of incorrect or extra items to a customer which does not get reported by the customer and is detected as a loss during stock-take. The risk to public health may differ compared to the pilfering example as the customer (such as pharmacist or dentist) may be appropriately qualified for the category of medicine supplied onwards and will be holding the medicine in appropriate conditions.

It is not uncommon for stock to be temporarily unaccounted for in companies that have many product lines, stock movements and consignments shipped daily, and these are often not reported until confirmed as definitely missing. The burden of reporting may drive such losses to be under-reported and only evident during stock-take, at which time the company writes-off the stock with no formal assessment - the main intention being to get the available stock numbers accurate. Stock written-off may become reported as damaged, under-supplied, or other category, without proper justification. This is not acceptable from a GDP perspective and the use of such false descriptors can lead to inappropriate risk awareness and preventive measurement development, which reduces the opportunity to improve processes and reduce wastage.

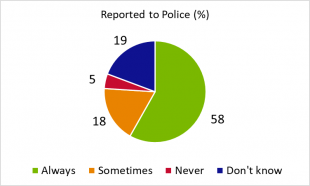

Q4. Do you report stolen medicines to the police?

Most delegates responded that medicine theft was always to be reported to the police. For those delegates who responded 'sometimes', it may be that the decision to report to the police was influenced by whether the theft took place away from their company's premises, if insurance claims were raised, or if reported to the Home Office.

The potential reasons for never reporting theft to the police could be due to several factors, such as type and value of stock or if theft occurred in another country.

Reporting stolen and missing medicines to MHRA

Why report to MHRA?

A main MHRA aim is to ensure that the medicines supply chain is safe and secure, so it is important that the risk of theft and diversion of medicines is managed in order to safeguard public health. It is therefore a GDP concern that incidents which pose significant risk are reported to MHRA, irrespective of whether they are reported to the police, Home Office or insurance companies. When reports are received, this enables the GDP inspectorate to look out for the stock and allows Intelligence and Enforcement departments to add this information to their database, which may help with separate cases.

When?

This depends on the event (missing or definitely stolen), product type, quantity and any other factor that influences risk to public health.

If it is deemed not to be a significant risk, then the justification for this decision should be included in your deviation report. Your quality risk management process should help identify what action to take - which may include reporting to MHRA.

For high-risk mislaid stock, it may be better to report this following initial investigation and then later report as found, rather than delay the reporting.

What?

Report:

- the date when the event was first noted

- products

- quantities

- batch numbers (if known)

- details of location

- contact details

- police incident number or Home Office reference, where relevant

How?

To report, please follow the links below:

Medicines enforcement

Whistleblower referrals

Coming up

In later blog posts I will look at applying standard GDP processes to develop a stronger security culture, plus security associated with transportation and storage.

Security will also be presented as a topic during the forthcoming GDP symposia (London and Glasgow) in November - so reserve the dates.

Don’t miss the next post, sign up to be notified by email when a new post comes out